Hidden Waters

- 2022

- This research was a collaboration between Nasim Razavian (studio ilinx), Jens Jorristma, Negar Sanaan Bensi and Paul Swagerman

- Research Funded by Stimuleringsfonds

The research is a case study on water systems and the conditions of thirst and abundance in two extreme geographies of the Iranian plateau and the Netherlands. It focuses on older complex systems and infrastructures of water in relation to their in-depth and interdisciplinary knowledge in the designs of the cities, infrastructures and architectural constructs around water.

The history of water management in Iran and the Netherlands provides an intriguing patchwork of diverse infrastructural systems and architectural entities, which not only have affected the formation of territories, but ‘the very possibility of life’ and a base for inhabitation. Both contexts, despite their extreme opposite conditions, share principles and concerns, as in both cases the idea of inhabiting a territory initially relies on managing water.

A series of analytical drawings were constructed based on the collection and investigation and tracing of different maps, drawings, photographs and texts that show the relations between multiple aspects and modes of knowledge expanding from geology of a place to structural engineering; from city planning to material sensibility, from water management to rituals and ceremonies; from hydraulic engineering to the growth of new ecologies and forms of life.

“Water is the most abundant element on the Earth and is also the most serious problem that humans have ever faced in the course of their history, a problem that used to overwhelm humans because of whether its influx or its scarcity.” (Semsar Yazdi el al. 2017)

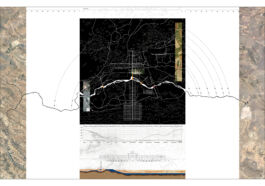

The drawings presented here, narrate different stories of water in the design of the 17th century (Safavid) city of Isfahan, and Khaju bridge as a protagonist in this story.

© Drawing by Nasim Razavian & Negar Sanaan Bensi, Hidden Waters Project, 2022

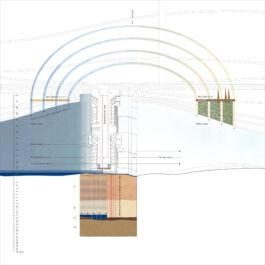

The drawing contains various concurrent scales inherent in the system of water: The 17th century Isfahan showing Zayandehroud river stemming from Mount Kuhrang and finishing at its terminal basin Gavkhuni Saltmarch, the complex relation between the system of Madis (canals) used for irrigation and washing the salty soil out of the city and pigeon towers as a contributor for soil fertilization. Then the Gardens as a result of soil fertility, system of bridges and the Khaju dam-bridge as a key to this system. The drawing also shows the monthly rainfall and fluctuations of the river, the strategic location of Khaju bridge in relation to the geological section of the soil, and house wells.

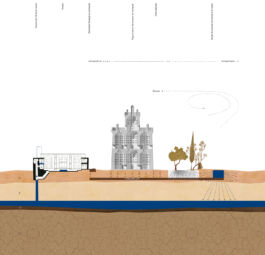

© Drawing by Nasim Razavian, Hidden Waters Project, 2022

The reconstruction of the system of water in Isfahan in multiple layers of below ground, on the ground and air. The drawing shows a house in Isfahan (Qodsi house) with a fresh water well, its sewage pit, a pigeon tower as the source for natural compost common in Isfahan and a section of a Madi (canal) which allows the water to penetrate through the sticky top soil and reach the roots of trees and move downwards towards the underground reservoir.

- A: Alluvial and flood plain deposits consisting of silt and sticky clay mud

- B: Soft aeolian sand which keeps underground water reservoirs

- C1: Dark shale and sandstone soil which is integrated and impenetrable

- C2: Dark shale and sandstone soil which is dry and has cracks through which water can escape

© Drawing by Nasim Razavian, Hidden Waters Project, 2022

The drawing shows Zayandeh Rud river, schematic representation of the Madis, Isfahan’s peculiar soil section, Khaju Bridge as a key to the water system and its foundation which acts as an underground dam for the water reservoir. The drawing also refers to the wind tunnels that the architecture of Khaju bridge creates and its effects on temperature as well as the speed of water. The drawing has multiple scales and the soil section is scaled up due to its importance.

- A: Alluvial and flood plain deposits consisting of silt and sticky clay mud

- B: Soft aeolian sand which keeps underground water reservoirs

- C1: Dark shale and sandstone soil which is integrated and impenetrable

- C2: Dark shale and sandstone soil which is dry and has cracks through which water can escape

© Drawing by Nasim Razavian, Hidden Waters Project, 2022

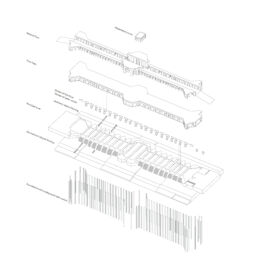

Exploded view of Khaju bridge showing the structure of the bridge, its foundation acting as an underground dam, sloped flooring on the riverbed, sluices that transformed the river into a lake and other structures.

© Drawing by Nasim Razavian, Hidden Waters Project, 2022

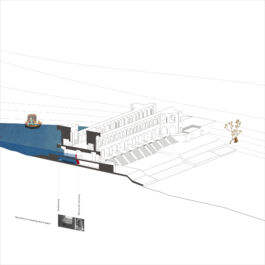

Sectioned view of Khaju bridge showing multiple operations that slow down the river’s speed of water such as swallowing, friction, damming, zigzagging, and falling in two conditions:

(A) Closed sluices in the canals (on the riverbed level) and first floor

(B) Closed sluices in the canals (on the riverbed level) / Open sluices when the river’s level of water is high

© Drawing by Nasim Razavian, Hidden Waters Project, 2022

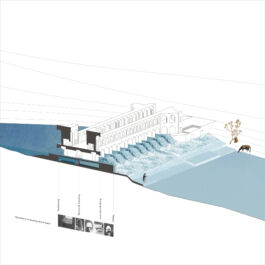

A reconstruction of the basement of Khaju bridge, the canals under the bridge, its plinths with their peculiar geometry, the steps and the sloped riverbed floorings stretching on the two sides of the bridge. The drawing shows the situation when the water level of the river is low and the sluices are opened. The bridge applies different hydraulic operations to slow down the water and creates peculiar forms and geometries of flows. At the entrance of the canals, the boat-shaped plinths cut the water flow with their pointy form. At the exit of the canals, the triangular forms of water intersect with each other on the horizontal surface and because of their different heights and slopes of flow they intersect vertically as well. The destructive power of water is transformed into thermal energy and the water-on-water fictions not only protect materials from erosion but they create air bubbles making it a great ecology for the life of fish and other forms of life.